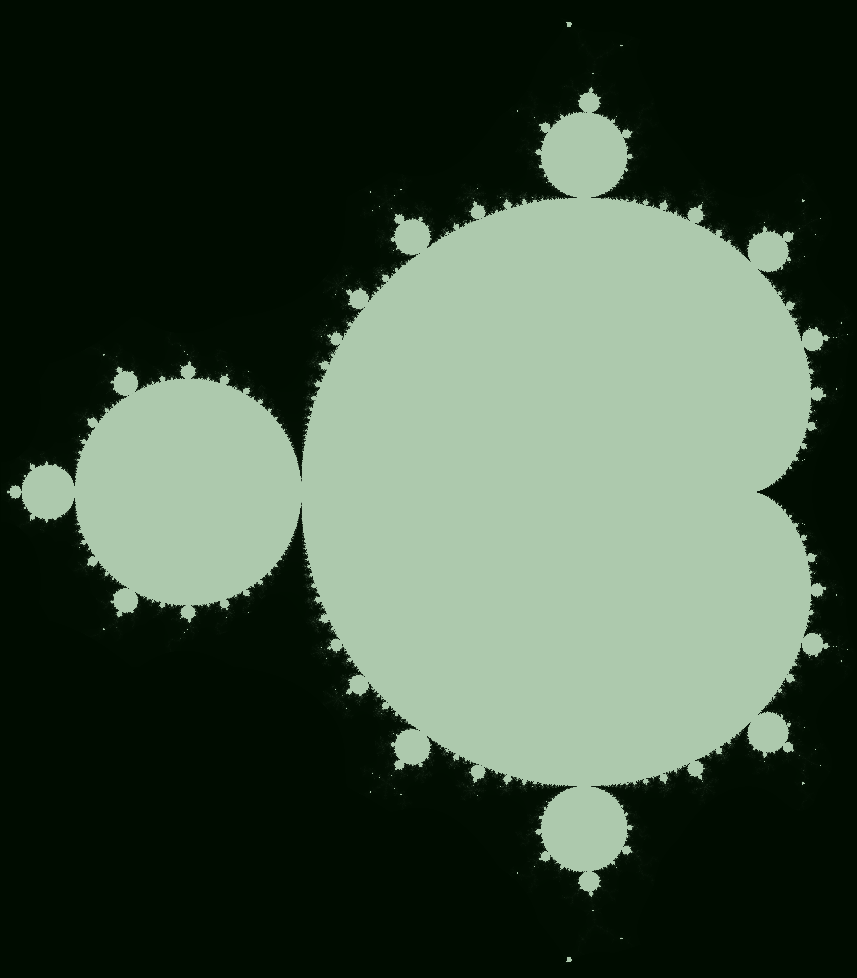

Mandelbrot set. Crunching numbers with SSE, AVX and OpenCL

The Mandelbrot set is the set of complex numbers \(c\) for which the function \(f_{c}(z)=z^{2}+c\) does not diverge when iterated from \(z=0\), i.e., for which the sequence \(\{ f_{c}(0),\>f_{c}(f_{c}(0)),\>\dots \}\) remains bounded in absolute value.

Usefull fact: if \(\|P_{c}^{n}(0)\| > 2\) - than that complex number \(c\) does not belong to the Mandelbrot set.

If \(c=(x_0, y_0) = x_0 + y_0 \cdot i\) and \(z=(x, y) = x + y \cdot i\), than \(f_{c}(z) = z^2+c\) \(= x^2 + 2 x y \cdot i - y^2 + x_0 + y_0 \cdot i\) \(= (x^2 - y^2 + x_0, 2xy + y_0)\).

We want to highlight such points on \(2D\) plane that corresponding complex numbers belongs to the Mandelbrot set (pseudocode):

mandelbrotContains(x0, y0):

x, y = x0, y0

for iteration in 0...MAX_ITERATIONS:

x, y = x*x - y*y + x0, 2*x*y + y0

if sqrt(x*x+y*y) > 2:

return false

return true

drawMandelbrot(image):

for x in image:

for y in image:

if mandelbrotContains(x, y):

image[x, y] = true

else:

image[x, y] = false

Let’s implement and tune performance of function, that calculates required number of iterations per pixel in mandelbrotContains(x, y) function. If that number is equal to MAX_ITERATIONS -

that pixel belongs to the Mandelbrot set.

Implementation on C++ looks like this:

void MandelbrotProcessorCPU::process(Vector2f from, Vector2f to,

Image<unsigned short>& iterations) {

size_t width = iterations.width;

size_t height = iterations.height;

float x_step = (to.x() - from.x()) / width;

float y_step = (to.y() - from.y()) / height;

for (size_t py = 0; py < height; py++) {

float y0 = from.y() + y_step * py;

for (size_t px = 0; px < width; px++) {

float x0 = from.x() + x_step * px;

unsigned short iteration;

float x = 0.0f;

float y = 0.0f;

for (iteration = 0; iteration < MAX_ITERATIONS; iteration++) {

float xn = x * x - y * y + x0;

y = 2 * x * y + y0;

x = xn;

if (x * x + y * y > INFINITY) {

break;

}

}

iterations(py, px) = iteration;

}

}

}

Notes: from and to are the coordinates of image corners on complex plane, INFINITY - divergence threshold (it is equal to 2.0f).

For all following benchmarking I will run

this

executable, but for 2048x2048 image (MAX_ITERATIONS = 10000 like on github).

On my Intel i7 6700 this implementation runs for 5545 ms.

OpenMP parallelization

But this CPU has 4 cores, and 8 threads because of hyper-threading, so let’s crunch numbers in 8 threads by using OpenMP with adding only single line of code! Code:

void MandelbrotProcessorCPU::process(Vector2f from, Vector2f to,

Image<unsigned short>& iterations) {

size_t width = iterations.width;

size_t height = iterations.height;

float x_step = (to.x() - from.x()) / width;

float y_step = (to.y() - from.y()) / height;

// The only line needed to add:

#pragma omp parallel for

for (size_t py = 0; py < height; py++) {

float y0 = from.y() + y_step * py;

for (size_t px = 0; px < width; px++) {

float x0 = from.x() + x_step * px;

unsigned short iteration;

float x = 0.0f;

float y = 0.0f;

for (iteration = 0; iteration < MAX_ITERATIONS; iteration++) {

float xn = x * x - y * y + x0;

y = 2 * x * y + y0;

x = xn;

if (x * x + y * y > INFINITY) {

break;

}

}

iterations(py, px) = iteration;

}

}

}

The only important line here is #pragma omp parallel for. OpenMP provides possibility to parallelize your code by inserting such simple pragmas.

It is supported by most compilers (maybe only on Mac OS X it is not available out of the box).

In this case OpenMP takes care of distributing workload between all available cores. It was asked to do so on outer for-loop - so it will execute code-block of outer loop for some py on each thread.

For example for each 8th py code-block can be executed on Core#8, each 7th out of 8 py - on Core#7 and so on.

So expected speedup is up to x8 times.

The same benchmark shows 1274 ms. The speedup is 5545 ms / 1274 ms = x4.3. It is not close to x8 because there are in fact only 4 real cores.

Hyper-threading of single core can give benefit only when there are two parallel tasks that uses different execution resources of that core.

The bottle-neck here is purely computational - and this part of CPU cannot be magically duplicated by hyper-threading.

So the current results are:

Speedup Time Implementation Device

x4.3 1274 ms Naive CPU 8 threads

x1.0 5545 ms Naive CPU 1 thread

Cpu is Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700 CPU @ 3.40GHz (4 cores, 8 threads by hyper-threading)

SIMD, SSE

For a long time nearly all CPUs have extensions of SIMD instructions. SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) makes possible to do some operation simultaneously on multiple operands. For example such instructions can calculate sum of \(a_1,a_2,a_3,a_4\) and \(b_1,b_2,b_3,b_4\), so the result is \(c_1,c_2,c_3,c_4\), where \(c_i=a_i+b_i\). So if instructions operates with N operands - it can give speedup around xN times.

The most popular extensions are SSE, SSE2 and up to SSE4.2. Nowadays they are supported on nearly all typical CPUs and operates with 128-bits data. In case of processing 32-bit single-precision floating points it means up to x4 speedup in ideal case.

All modern compiles supports intrinsics for such extensions.

Example of SSE intrinsic is _mm_add_ps - it sums four floating point numbers (from processor’s SSE register) with another four floating point numbers (from another register) and

stores result in third register. More detailed description about all intrinsics can be found on very handy Intel intrinsics guide.

Note that suffix of intrinsic name represents type of operands data. For example ps - for single-precision floating points, pi16 - 16-bits integers and so on.

Because intrinsics works with 4 32-bits operands at time - we should do our computations in CPU registers, than unload data from result register to memory.

C++ compiler will take care about mapping of our computations into registers, but we should help him by explicitly working with 4 values at time - by using special type: __m128 - 128-bits register.

Final code:

void MandelbrotProcessorCPU_SSE::process(Vector2f from, Vector2f to,

Image<unsigned short>& iterations) {

float width = iterations.width;

float height = iterations.height;

float x_step = (to.x() - from.x()) / width;

float y_step = (to.y() - from.y()) / height;

#pragma omp parallel for

for (size_t py = 0; py < iterations.height; py++) {

float y0 = from.y() + y_step * py;

for (size_t px = 0; px < iterations.width / 4 * 4; px += 4) {

float pxf = (float) px;

// Four values in register (__m128):

__m128 pxs_deltas128 = _mm_mul_ps(_mm_set_ps(0.0f, 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f), _mm_set1_ps(x_step)); // 0.0f*x_step, 1.0f*x_step, 2.0f*x_step, 3.0f*x_step

__m128 xs0 = _mm_add_ps(_mm_set1_ps(from.x()), _mm_add_ps(_mm_set1_ps(x_step * pxf), pxs_deltas128)); // from.x()+px*x_step, where px takes 4 conseqent values starting from current loop index

unsigned short iteration;

__m128i maskAll = _mm_setzero_si128(); // maskAll is the mask, that stores flag for each value from our four:

__m128i iters = _mm_setzero_si128(); // 'is this series divergent?' - sqrt(x*x+y*y) > 2

__m128 xs = _mm_set1_ps(0.0f); // because in that case we should not increment 'iters' for that value

__m128 ys = _mm_set1_ps(0.0f);

for (iteration = 0; iteration < MAX_ITERATIONS; iteration++) {

__m128 xsn = _mm_add_ps(_mm_sub_ps(_mm_mul_ps(xs, xs), _mm_mul_ps(ys, ys)), xs0); // xn = x * x - y * y + x0;

__m128 ysn = _mm_add_ps(_mm_mul_ps(_mm_mul_ps(_mm_set1_ps(2.0f), xs), ys), _mm_set1_ps(y0)); // yn = 2 * x * y + y0;

xs = _mm_add_ps(_mm_andnot_ps((__m128) maskAll, xsn), _mm_and_ps((__m128) maskAll, xs)); // updating previous values to new ones

ys = _mm_add_ps(_mm_andnot_ps((__m128) maskAll, ysn), _mm_and_ps((__m128) maskAll, ys)); // but with taking into account maskAll

// (if value divergent once - we should fix its iterations number)

maskAll = _mm_or_si128(_mm_castps_si128(_mm_cmpge_ps(_mm_add_ps(_mm_mul_ps(xs, xs), _mm_mul_ps(ys, ys)), _mm_set1_ps(INFINITY))), maskAll); // calculating mask, by checking x*x+y*y > INFINITY for each value

iters = _mm_add_epi16(iters, _mm_andnot_si128(maskAll, _mm_set1_epi16(1))); // increments 'iters' counter for those numbers,

int mask = _mm_movemask_epi8(maskAll); // that were taking part in this iteration

if (mask == 0xffff) {

break; // if all values divergent - stop

}

}

iters = _mm_shuffle_epi8(iters, _mm_setr_epi8(12, 13, 8, 9, 4, 5, 0, 1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1, -1));

_mm_storel_epi64((__m128i *) &iterations(py, px), iters); // unloading data to memory

}

for (size_t px = iterations.width / 4 * 4; px < iterations.width; px++) {

float x0 = from.x() + (to.x() - from.x()) * px / width;

unsigned short iteration;

float x = 0.0f;

float y = 0.0f;

for (iteration = 0; iteration < MAX_ITERATIONS; iteration++) {

float xn = x * x - y * y + x0;

y = 2 * x * y + y0;

x = xn;

if (x * x + y * y > INFINITY) {

break;

}

}

iterations(py, px) = iteration;

}

}

}

Yes! Such a mess! Coding is very slow (of course if you do it only at times). Intel intrinsics guide helps a lot - it has very good filters by extensions (for example you may not wanting suddenly use AVX because not all of your consumers have CPU that supports it), provides very strict descriptions and so on.

Note, that the final for-loop is a fallback to naive CPU version, because we may have number of data that is not a multiple of 4 and this way is the simplest one to deal with that values.

Performance results (in fact SSE, SSE2 and SSSE3 were used):

Speedup Time Implementation Device

x10.1 547 ms CPU SSE 8 threads

x2.3 2370 ms CPU SSE 1 thread

x4.3 1274 ms Naive CPU 8 threads

x1.0 5545 ms Naive CPU 1 thread

Cpu is Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700 CPU @ 3.40GHz (4 cores, 8 threads by hyper-threading)

SIMD, AVX

But we can go futher! After SSE new important instructions extension was AVX (proposed in 2008, supported since 2011 in Sandy Bridge).

The main difference is wider registers - 256-bits wide, so it can be twice faster! Note, that when code is adopted to SSE usage - adoptation to AVX

is quite straightforward - just replace __m128 with __m256 and update code to minor functions changes (for example sometimes order of arguments changes).

Code is nearly the same as for SSE, but anyway:

void MandelbrotProcessorCPU_AVX::process(Vector2f from, Vector2f to,

Image<unsigned short>& iterations) {

assert (MAX_ITERATIONS < std::numeric_limits<unsigned short>::max());

assert (iterations.cn == 1);

assert (((float) iterations.width) + 1 == (float) (iterations.width + 1));

assert (((float) iterations.height) + 1 == (float) (iterations.height + 1));

float width = iterations.width;

float height = iterations.height;

float x_step = (to.x() - from.x()) / width;

float y_step = (to.y() - from.y()) / height;

#pragma omp parallel for

for (size_t py = 0; py < iterations.height; py++) {

float y0 = from.y() + y_step * py;

for (size_t px = 0; px < iterations.width / 8 * 8; px += 8) {

float pxf = (float) px;

__m256 pxs_deltas128 = _mm256_mul_ps(_mm256_set_ps(0.0f, 1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f, 5.0f, 6.0f, 7.0f), _mm256_set1_ps(x_step));

__m256 xs0 = _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_set1_ps(from.x()), _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_set1_ps(x_step * pxf), pxs_deltas128)); // from.x() + x_step * px

unsigned short iteration;

__m256i maskAll = _mm256_setzero_si256();

__m256i iters = _mm256_setzero_si256();

__m256 xs = _mm256_set1_ps(0.0f);

__m256 ys = _mm256_set1_ps(0.0f);

for (iteration = 0; iteration < MAX_ITERATIONS; iteration++) {

__m256 xsn = _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_sub_ps(_mm256_mul_ps(xs, xs), _mm256_mul_ps(ys, ys)), xs0); // xn = x * x - y * y + x0;

__m256 ysn = _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_mul_ps(_mm256_mul_ps(_mm256_set1_ps(2.0f), xs), ys), _mm256_set1_ps(y0)); // yn = 2 * x * y + y0;

xs = _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_andnot_ps((__m256) maskAll, xsn), _mm256_and_ps((__m256) maskAll, xs));

ys = _mm256_add_ps(_mm256_andnot_ps((__m256) maskAll, ysn), _mm256_and_ps((__m256) maskAll, ys));

maskAll = (__m256i) _mm256_or_ps(_mm256_cmp_ps(_mm256_add_ps(_mm256_mul_ps(xs, xs), _mm256_mul_ps(ys, ys)), _mm256_set1_ps(INFINITY), _CMP_GT_OS), (__m256) maskAll);

iters = _mm256_add_epi16(iters, _mm256_andnot_si256(maskAll, _mm256_set1_epi16(1)));

int mask = _mm256_movemask_epi8(maskAll);

if (mask == (int) 0xffffffff) {

break;

}

}

iters = _mm256_shuffle_epi8(iters, _mm256_setr_epi8(0, 1, -1, -1, 4, 5, -1, -1, 8, 9, -1, -1, 12, 13, -1, -1, 16, 17, -1, -1, 20, 21, -1, -1, 24, 25, -1, -1, 28, 29, -1, -1));

unsigned int tmp[8];

_mm256_storeu_si256((__m256i *) tmp, iters);

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

iterations(py, px + 7 - i) = (unsigned short) tmp[i];

}

}

for (size_t px = iterations.width / 8 * 8; px < iterations.width; px++) {

float x0 = from.x() + (to.x() - from.x()) * px / width;

unsigned short iteration;

float x = 0.0f;

float y = 0.0f;

for (iteration = 0; iteration < MAX_ITERATIONS; iteration++) {

float xn = x * x - y * y + x0;

y = 2 * x * y + y0;

x = xn;

if (x * x + y * y > INFINITY) {

break;

}

}

iterations(py, px) = iteration;

}

}

}

Performance:

Speedup Time Implementation Device

x20.8 266 ms CPU AVX2 8 threads

x4.8 1160 ms CPU AVX2 1 thread

x10.1 547 ms CPU SSE 8 threads

x2.3 2370 ms CPU SSE 1 thread

x4.3 1274 ms Naive CPU 8 threads

x1.0 5545 ms Naive CPU 1 thread

Cpu is Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700 CPU @ 3.40GHz (4 cores, 8 threads by hyper-threading)

AVX really give x2 speedup over SSE.

OpenCL

OpenCL provides a uniform way to implement parallel computations that could be executed on many multi-core devices - GPUs and CPUs. The main code is in kernel source code with syntax based on C99 and kernels are compiled in runtime (like shaders for OpenGL). So the application sends source code to available OpenCL driver (for example GPU driver or special driver for CPU) to compile and execute kernels.

The code is very similar to naive CPU version:

__kernel void mandelbrotProcess(__global unsigned short* iterations,

int width, int height,

float fromX, float fromY, float toX, float toY) {

int px = get_global_id(0);

int py = get_global_id(1);

if (px >= width || py >= height) return;

float x0 = fromX + px * (toX - fromX) / width;

float y0 = fromY + py * (toY - fromY) / height;

unsigned short iteration;

float x = 0.0f;

float y = 0.0f;

for (iteration = 0; iteration < MAX_ITERATIONS; iteration++) {

float xn = x * x - y * y + x0;

y = 2 * x * y + y0;

x = xn;

if (x * x + y * y > INFINITY_THRESHOLD) {

break;

}

}

iterations[width * py + px] = iteration;

}

But the performance on AMD R9 390X is impressive - 6 ms! x924 speedup! The reason is the nature of executed task - it is ideal for parallel computations and the only bottle-neck is computations, no overhead for memory access, no if-else branching, only a lot of computations that can fit in registers and execution runs with full computation power of device. In case of AMD R9 390X raw power is 2816 cores running at 1 Ghz!

OpenCL kernels also can be run on CPUs - the test contains execution on i7-6700 via two OpenCL drivers: by Intel and by AMD (it supports Intel CPUs too):

Speedup Time Implementation Device

x924 6 ms OpenCL (AMD) Hawaii R9 390X

x22 252 ms OpenCL (Intel) Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700 CPU @ 3.40GHz

x5.8 942 ms OpenCL (AMD) Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700 CPU @ 3.40GHz

x20.8 266 ms CPU AVX2 8 threads

x4.8 1160 ms CPU AVX2 1 thread

x10.1 547 ms CPU SSE 8 threads

x2.3 2370 ms CPU SSE 1 thread

x4.3 1274 ms Naive CPU 8 threads

x1.0 5545 ms Naive CPU 1 thread

Cpu is Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700 CPU @ 3.40GHz (4 cores, 8 threads by hyper-threading)

And suddenly Intel driver performs better than AVX version! It means that it was able to successfully vectorize code using available on this CPU extensions: AVX and AVX2. AMD driver seems to just run given code on all available threads and it leads to the same performance level as naive parallelization.

OpenCL makes possible to use CPU and GPU power for parallel computations. And this is quite easy to code in comparison with CPU intrinsics usage. Even on CPU good performance often can be reached with just naive version of code compiled with OpenCL driver (Intel driver often able to vectorize code). But sometimes intrinsics required: if your consumers have no GPU and it is too hard for them to install Intel OpenCL driver, or if you have a lot of idle computers with powerful CPUs (for example idle servers with Xeons) and Intel driver was not able to vectorize your too complex code, and so on.